So you got a great deal when a diamond—or so you thought. But when you tried to sell it, or lost it and needed your insurance company to replace it, you suddenly discovered it’s worth much less than what you were led to believe.

After more than 33 years in the jewelry industry, this is and always has been one of my top pet peeves. While most retail jewelers are highly trustworthy, the few proverbial bad apples spoil the image of the whole bunch.

First let’s talk about the good ones: the stores that you grew up with, the trusted jeweler that has served your community for multiple generations, whose grandfather sold your grandparents their engagement ring, and so on. Your family jeweler is as much a part of your roster of professionals as your trusted doctor, lawyer, and accountant, and they’ve been there to help you celebrate all of life’s precious milestones.

But now let’s talk about the others: the ones screaming 50% off every diamond in the store or, worse, promising your jewelry will appraise for twice what you paid for it.

I have three words for that: Run. Like. Hell.

While the value of a diamond varies with its attributes, the Four C’s , there is a quantifiable range into which stones with similar attributes will fall. Nobody — or at least nobody that plans to remain in business — is selling a diamond for 50% less than it’s truly worth. I’ll say it again: nobody is selling a diamond for 50% less than it’s truly worth. It doesn’t take an MBA to figure out that’s not a viable business model.

There is a difference between a legitimate sale and a bogus discount. A reputable jewelry store might have an end-of-season sale, a moving or remodeling sale, a closeout of certain lines, a special promotion, or an inventory reduction sale. And estate jewelry can be a good value compared to a similar new piece. All those are much different than a store whose entire business model is based on making you think you’re getting more than you’re paying for.

The Federal Trade Commission is very particular about that, says Sara Yood, an attorney for the Jewelers’ Vigilance Committee, which is the industry’s legal watchdog organization. The FTC has specific regulations surrounding both “regular” and “manufacturer’s suggested retail” pricing (MSRP) vs. discounted pricing.

“16 CFR § 233.1 etc. states: ‘If the former price is the actual, bona fide price at which the article was offered to the public on a regular basis for a reasonably substantial period of time, it provides a legitimate basis for the advertising of a price comparison.’” But the Guide does not define what a ‘substantial’ period of time means, explains Yood. “It does say, however, that an item need not to have actually sold any at the offered price for the discount to be valid; it just has to have been offered.”

In the case of MSRP, FTC section 16 CFR § 233.3 explains that many members of the public do believe that the MSRP is the price at which an article is generally sold, and that a reduction from that price is a bargain. But unless a substantial number of sales of the article are made at MSRP, advertising a discount can be misleading—and retailers must be careful not to create a false impression of discount.

Those screaming discount ads have convinced consumers there are huge markups on diamond jewelry, but in reality diamond margins are less than 50%: much, much lower than the typical markup on apparel, handbags, or shoes.

Unfortunately, unsuspecting consumers don’t know that inflated appraisals are a popular marketing ploy, so when they go to sell their ring later and find out its retail value is not what they were told, they tend to blame the jeweler or appraiser that gave them the bad news, not the original seller that gave the inflated appraisal.

If a discount seems too good to be true but you love the ring, at least know what you’re buying. If you buy a diamond ring for $1,000 and the appraisal says it’s worth $2,000, take it to another qualified jeweler or appraiser (we’ll get to that shortly), and get a second opinion. I would bet the farm it will be worth $1,000—exactly what you paid for it. Maybe it’ll be valued a little higher, but it won’t be valued at $2,000.

If you find out it’s worth less than you paid for it, that’s a whole other situation with possible legal ramifications. First, get a third opinion as soon as possible. If two independent appraisals come in much lower than what the seller claims, you can try to return the ring or ask the seller to refund the difference.

This is where it can get murky, though, because retailers have the right to set any return policy they want so long as it’s clearly communicated to the consumer, says Sara Yood. JVC handles these types of situations in its mediation practice, but she cautions that restitution hinges on whether the consumer was economically harmed.

“Let’s say the consumer thought they were purchasing a diamond with E color and VS1 clarity, and a third-party appraiser said it was actually a K color SI1 diamond. But the consumer paid an amount that really corresponds to a K SI1. In that case, there was no economic harm, so there’s no case. But if the consumer paid for the equivalent of an E VS1, then there is likely economic harm and that is a case we could possibly mediate so that the costs were kept down for the consumer and they wouldn’t need to hire a lawyer.

Another key point to understand is the difference between weight and total weight. Knowing how carat weight and total carat weight work is crucial in understanding how diamonds are priced. A ring with a large center stone is significantly more valuable than one with a lot of small stones, even if the weight of the smaller stones adds up to the same carat weight as the single big stone.

Why is that? Because large stones are far rarer than small stones, so they’re worth much more. The diamond value equation is exponential, not linear: a two-carat diamond is much rarer than a one-carat diamond—and greatly much rarer than a half-carat diamond. Assuming all the other aspects (color, cut, and clarity) are equal, a ring with a single two-carat stone is going to be worth far more than a ring with a one-carat center and one carat’s worth of small accent stones, such as might be found in a halo setting. And it’s going to be worth far, far, more than a ring with a cluster of 20 0.10-carat stones and no center stone. Yet all have a finished weight of two carats.

Here’s how to understand the industry acronyms. CW is short for carat weight, meaning the weight of an individual stone in carats (1 carat is the equivalent of 0.2 grams). This is also sometimes abbreviated as DW, or “diamond weight,” or just the number of carats. So if you see a listing with “1CW,” or “1.0 CT,” you know it’s likely to be a single stone ring with a one carat diamond.

By contrast, total carat weight is abbreviated CTW, meaning the total weight of all the diamonds on the ring, in carats. It can also be abbreviated as TDW, which means “total diamond weight,” or, occasionally, TCW. Whatever version is used, the number is just a sum. It says nothing about how many stones are on the ring, or their individual sizes. A ring labeled “1.0 CTW” could have four stones of 0.25 CT each, or 10 of 0.10 CT each. Again, all other things being equal—color, cut, clarity—the ring with four quarter-carat stones is going to be more valuable than the one with 10 0.10-CW stones.

Does it matter if your jewelry has a certificate from an independent third-party gemological lab or only from the jeweler where you bought it?

A certificate from a gemological lab is always going to be preferred, but a qualified jeweler—emphasis on qualified—can provide an acceptable certificate as well.

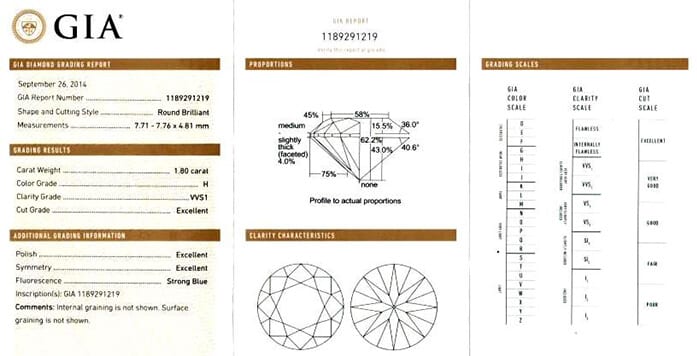

Today, most better jewelers generally will automatically provide a laboratory grading certificate with any stone over about one-third of a carat anyway, so it’s often a non-issue. And when you sell a stone through Worthy.com, we send it to a third-party grading lab like GIA (Gemological Institute of America).

But what about those few jewelers that still prefer to grade a stone themselves? Or older stones that have been handed down in the family and have only a jeweler’s grading?

That’s okay, provided the jeweler has the qualifications to do a proper evaluation. You want to make sure the jeweler grading your stone holds a graduate gemologist title (G.G.), earned from GIA after extensive study and testing. Equally valid are certified gemologist (C.G.) or certified gemologist appraiser (C.G.A.) titles from the American Gem Society. (Typically, most jewelers that have passed AGS’s rigorous C.G. and C.G.A. exams also have their G.G. diploma from GIA.) Other organizations that confer respected accreditation are the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (designated as FGA), and the American Society of Appraisers (ASA).

Other industry designations, such as from Jewelers of America or Diamond Council of America, may show a jeweler or sales associate has had training to sell jewelry but is not a graduate gemologist. (Compare to buying a car: a good salesperson knows everything about the car’s performance relative to your needs, but isn’t a mechanic.)

Finally, be aware that a grading certificate is not the same as an appraisal! A gem lab grading certificate states what the stone’s physical properties are — but the value of those properties comes from comparing the stone’s report with established industry price ranges at the time. A qualified jeweler can easily look up that data and give you a proper valuation with your certificate. Other factors, such as a one-of-a-kind setting or a famous brand name, can also impact that value.

The bottom line? If a deal seems too good to be true, get a second opinion. You will have to pay for an independent grading or appraisal, but it’s better to pay a few hundred dollars now than risk losing thousands later.

©2011-2025 Worthy, Inc. All rights reserved.

Worthy, Inc. operates from 25 West 45th St., 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10036